Numerical Analysis of the Kolmogorov Equations

Uffe Høgsbro Thygesen

2025-12-05

Source:vignettes/NumericalKolmogorov.Rmd

NumericalKolmogorov.RmdThe Kolmogorov equationsa are central in the theory of stochastic differential equations, as they govern the transition probabilities of the solutions to these equations. See (Thygesen 2023) for background theory, including the derivation of the equations and their application in many types of analysis of stochastic differential equations.

In this vignette, we consider the numerical analysis of the forward and backward Kolmogorov equation, using the fvade function (Finite Volume method for Advection-Diffusion Equations).

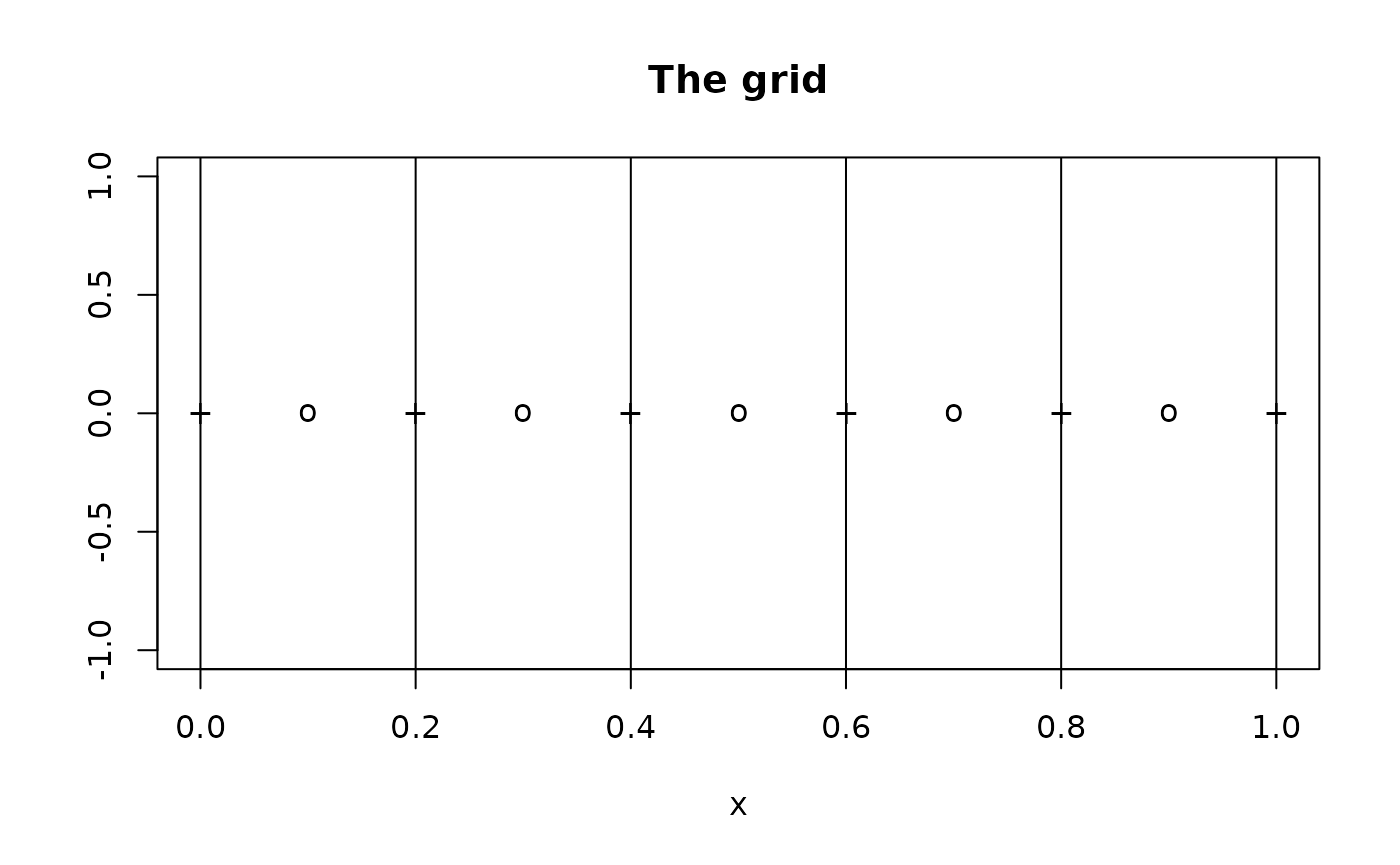

Let us start with a toy example. We make a uniform grid on the unit interval with four grid cells, i.e. five cell boundaries:

## Loading required package: SDEtools

xi <- seq(0,1,0.2)

xc <- cell.centers(xi)

plot(xi,0*xi,pch="+",xlab="x",ylab="",main="The grid")

for(x in xi) abline(v=x)

points(xc,0*xc,pch="o")

We consider standard Brownian motion on this interval, i.e. with reflection at the boundaries, :

u <- function(x) 0

D <- function(x) 0.5

Gd <- fvade(u,D,xi,'r')## Loading required package: Matrix

print(Gd)## 5 x 5 sparse Matrix of class "dgCMatrix"

##

## [1,] -12.5 12.5 . . .

## [2,] 12.5 -25.0 12.5 . .

## [3,] . 12.5 -25.0 12.5 .

## [4,] . . 12.5 -25.0 12.5

## [5,] . . . 12.5 -12.5Note that the discretized version is tri-diagonal (we only jump the neighbouring states) and symmetric (because the Laplacian is self-adjoint and the grid is uniform). There is a constant rate of jumps to “right” cells and the same jump rate to “left” cells, whenever these cells exist. As a result, the sojourn time - which is found as one divided with the diagonal entries - is smaller in inner cells than in boundary cells.

Next, consider pure advection, with constant flow field +1 and no diffusion: We still use reflection at the boundaries. From a mathematical point of view, the boundary becomes a singularity where probability “piles up”. The discretized equations are:

## 5 x 5 sparse Matrix of class "dgCMatrix"

##

## [1,] -5 5 . . .

## [2,] . -5 5 . .

## [3,] . . -5 5 .

## [4,] . . . -5 5

## [5,] . . . . .Note that this corresponds to a Markov chain where we only jump right, so that the rightmost cell becomes absorbing. Similarly for a constant flow field -1:

## 5 x 5 sparse Matrix of class "dgCMatrix"

##

## [1,] . . . . .

## [2,] 5 -5 . . .

## [3,] . 5 -5 . .

## [4,] . . 5 -5 .

## [5,] . . . 5 -5Solution using the matrix exponential

We now consider the forward Kolmogorov equation

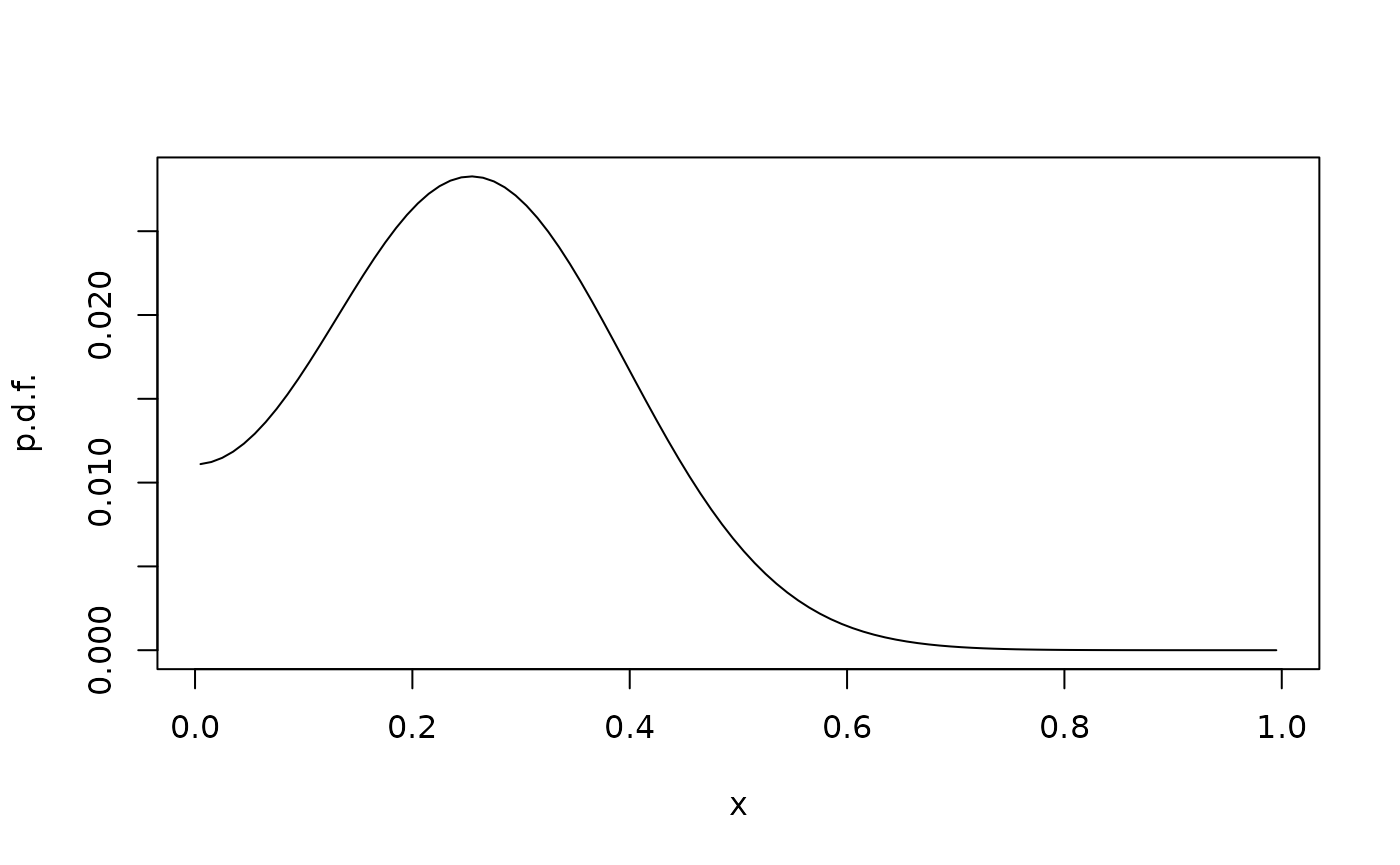

on with reflection at the boundary , corresponding to reflected Brownian motion with intensity . We solve this using the matrix exponential. This avoids errors arising from time discretization, but is expensive for large matrices.

xi <- seq(0,1,0.01)

xc <- cell.centers(xi)

G <- fvade(function(x)0,function(x)1,xi,'r')

t <- 0.01

x0 <- 0.25

phi0 <- diff(xi > x0)

phit <- phi0 %*% expm(G*t)

plot(xc,phit,type="l",xlab="x",ylab="p.d.f.")

Note that a probability vector must be multiplied on (and by extension, on ) from the left.

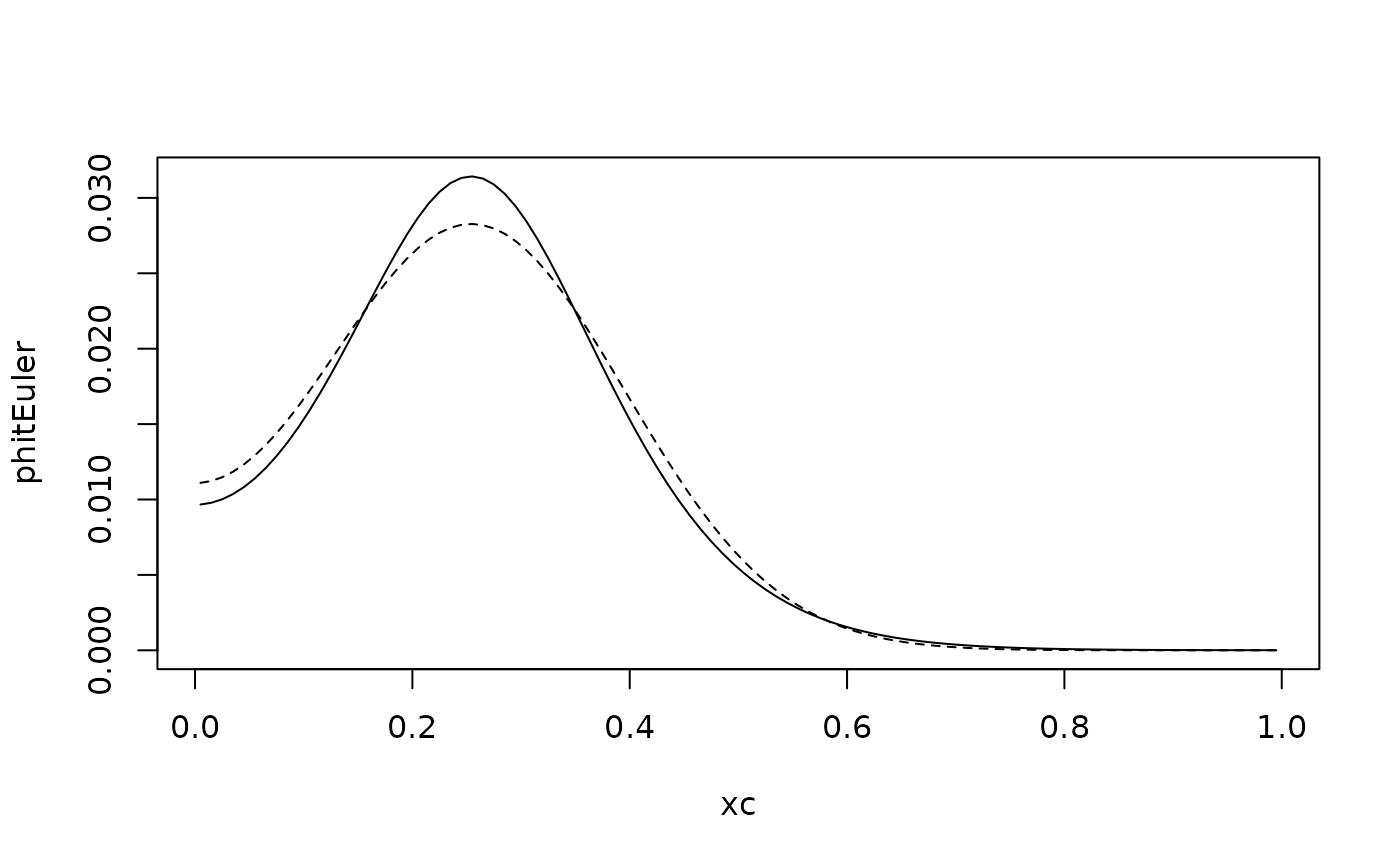

Implicit Euler stepping

The matrix exponential is computationally expensive. A simpler solution is to use an Euler scheme. Explicit Euler is a bad idea, as it requires a very small time step for stability. So here we use an implicit Euler step:

I <- Diagonal(length(xc))

n <- 4

IGt <- t(I - t/n*G)

phitEuler <- solve(IGt,phi0)

for(i in 2:n) phitEuler <- solve(IGt,phitEuler)

plot(xc,phitEuler,type="l")

lines(xc,phit,lty="dashed")

The solver uses the sparsity of the system, so it is quite effective. Note that the time step we used the Euler method here is quite large, so that the time discretization error is visible.

Periodic boundaries

The previous was done with reflecting boundaries. This imposes that the flux at the boundary is zero. In this case, where there is only diffusion, it implies a homogenous Neumann boundary condition of the forward equation.

We can repeat the study with periodic boundary conditions:

G <- fvade(function(x)0,function(x)1,xi,'p')

phit <- phi0 %*% expm(G*t)

plot(xc,phit,type="l",xlab="x",ylab="p.d.f.")

Note that there now is a flux from the left boundary to the right.

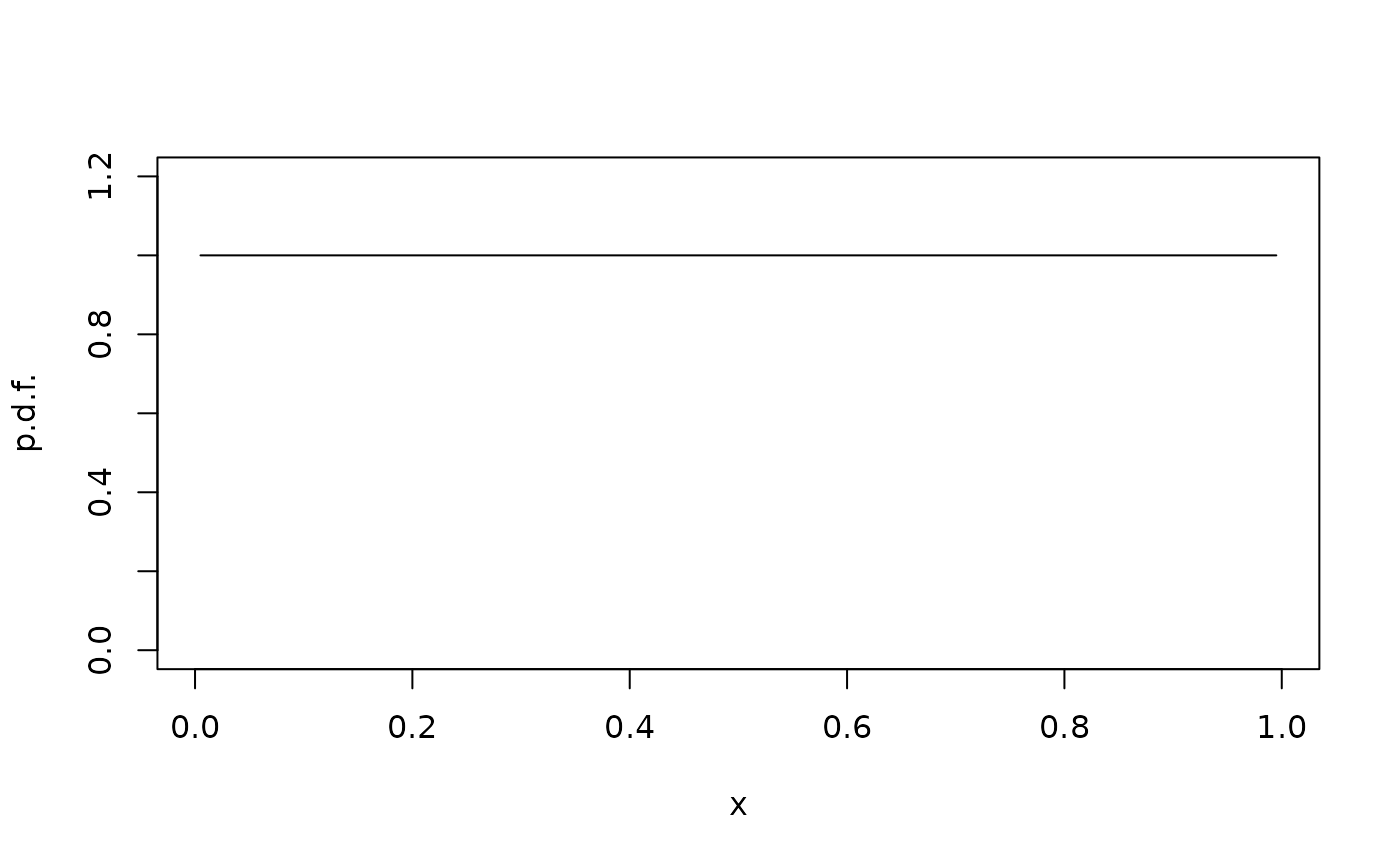

Whether we use periodic or reflecting boundaries, we can find the stationary distribution:

rho <- StationaryDistribution(G)

plot(xc,rho/diff(xi),type="l",ylim=c(0,1.2),xlab="x",ylab="p.d.f.")

As expected, the stationary distribution is uniform.

Absorbing boundaries

Finally, we can try absorbing boundaries. Here, we have two options: We can extend the state space with the absorbing boundary points; this would result in a Markov chain with 102 states (100 inner states and the two boundary states). In the following, in stead we omit the boundary.

G <- fvade(function(x)0,function(x)1,xi,'a')

phit <- phi0 %*% expm(G*t)

plot(xc,phit,type="l",xlab="x",ylab="p.d.f.")

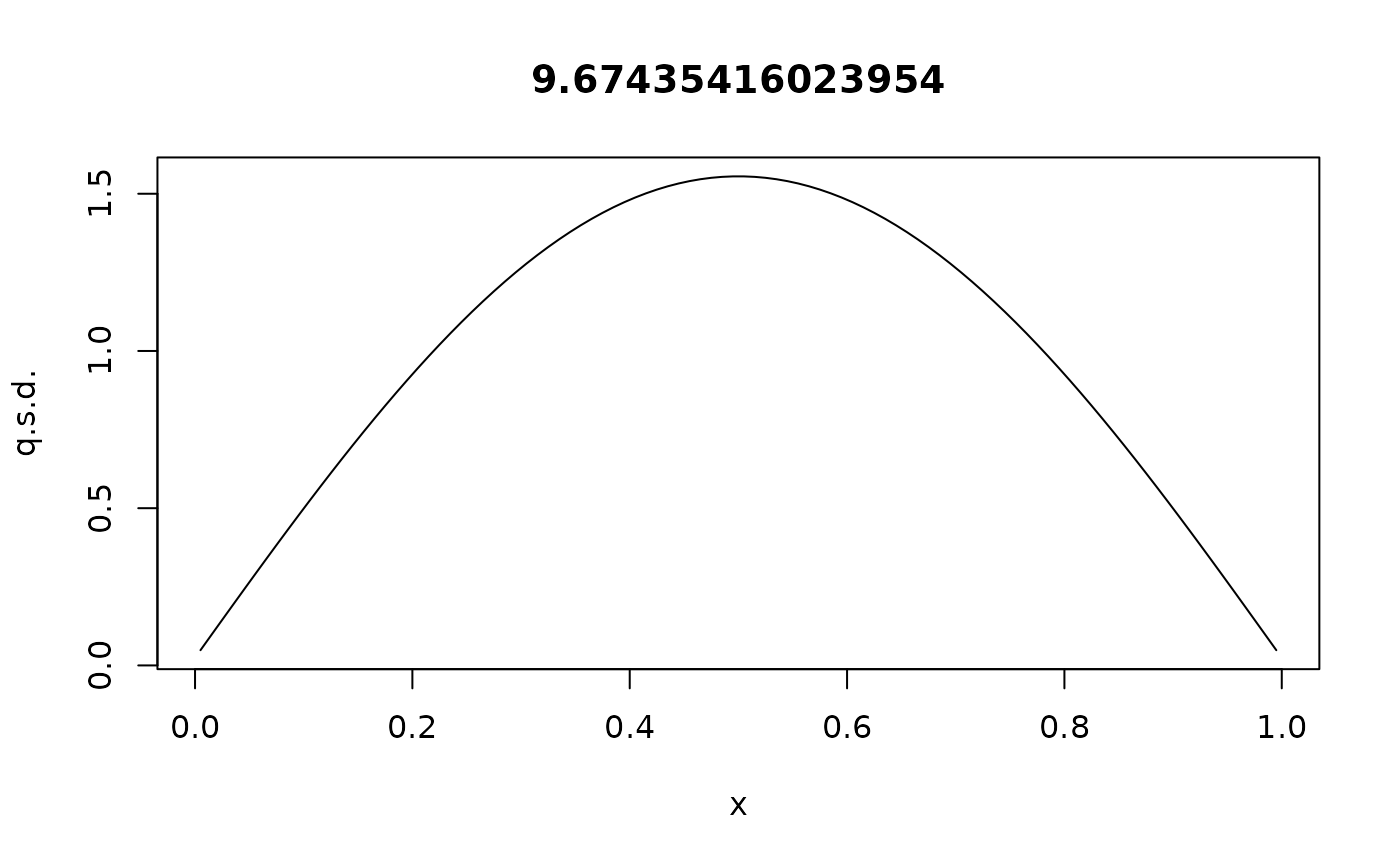

With absorbing boundaries, the probability inside the domain is not conserved, but will eventually vanish. So there is no stationary distribution, but a quasistationary distribution:

rho <- QuasiStationaryDistribution(G)

plot(xc,rho$vector/diff(xi),type="l",main=rho$value,xlab="x",ylab="q.s.d.")

Theoretically, this should be (normalized) and the corresponding eigenvalue is , i.e., the expected time to absorption is roughly 0.1 time units, in the quasistationary state.

Including both advection and diffusion

We now include advection: Add a flow field that directs towards the center.

u <- function(x) 16*(0.5-x)

D <- function(x) 1

G <- fvade(u,D,xi,'r')As before, the advection is discretized with a first order upwind scheme:

## 4 x 4 sparse Matrix of class "dgCMatrix"

##

## [1,] -10784 10784 . .

## [2,] 10000 -20768 10768 .

## [3,] . 10000 -20752 10752

## [4,] . . 10000 -20736## 4 x 4 sparse Matrix of class "dgCMatrix"

## [,97] [,98] [,99] [,100]

## [97,] -20736 10000 . .

## [98,] 10752 -20752 10000 .

## [99,] . 10768 -20768 10000

## [100,] . . 10784 -10784Note that the advection adds extra jumps in the direction of the advection. This way of discretizing is quite coarse and introduces numerical diffusion, but it has some important advantages: The discretized system is the generator of a Markov chain, and this generator is a linear combination of a generator for the diffusion and one for the advection. These features make the technique robust and suitable for demonstration. In a specific application, it could be worthwhile to explore higher-order methods, but then it must be carefully checked what properties the discretized system has, and what the consequences of this are.

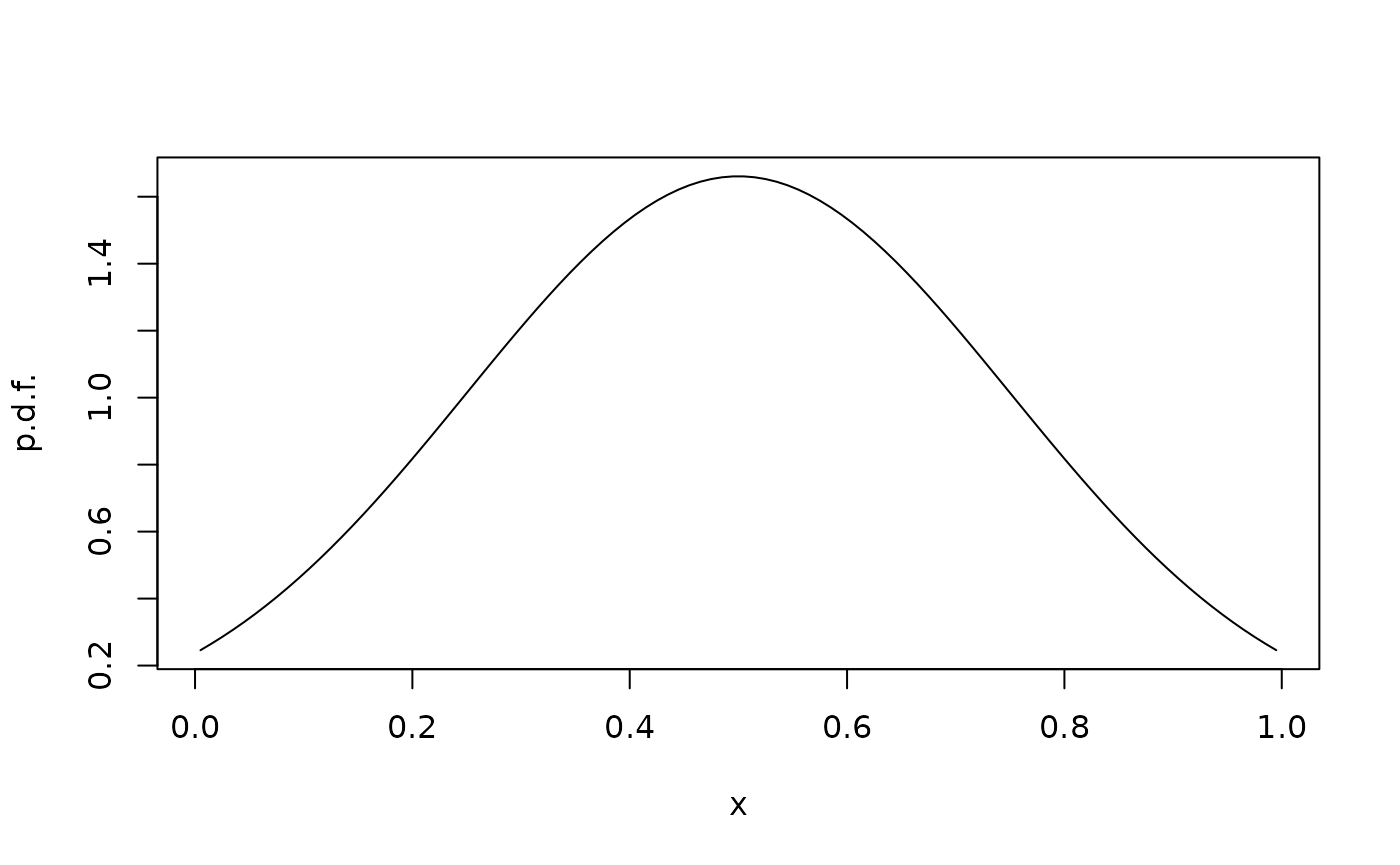

We can again plot the stationary distribution:

rho <- StationaryDistribution(G)

plot(xc,rho/diff(xi),type="l",xlab="x",ylab="p.d.f.")

Without boundaries, this would be a Gaussian with mean 0.5 and variance , i.e. standard deviation . This is visible in the solution, although the effect of the boundaries perturb the solution. Note also that with advection, the no-flux boundary condition is no longer the same as a homogeneous Neumann condition.

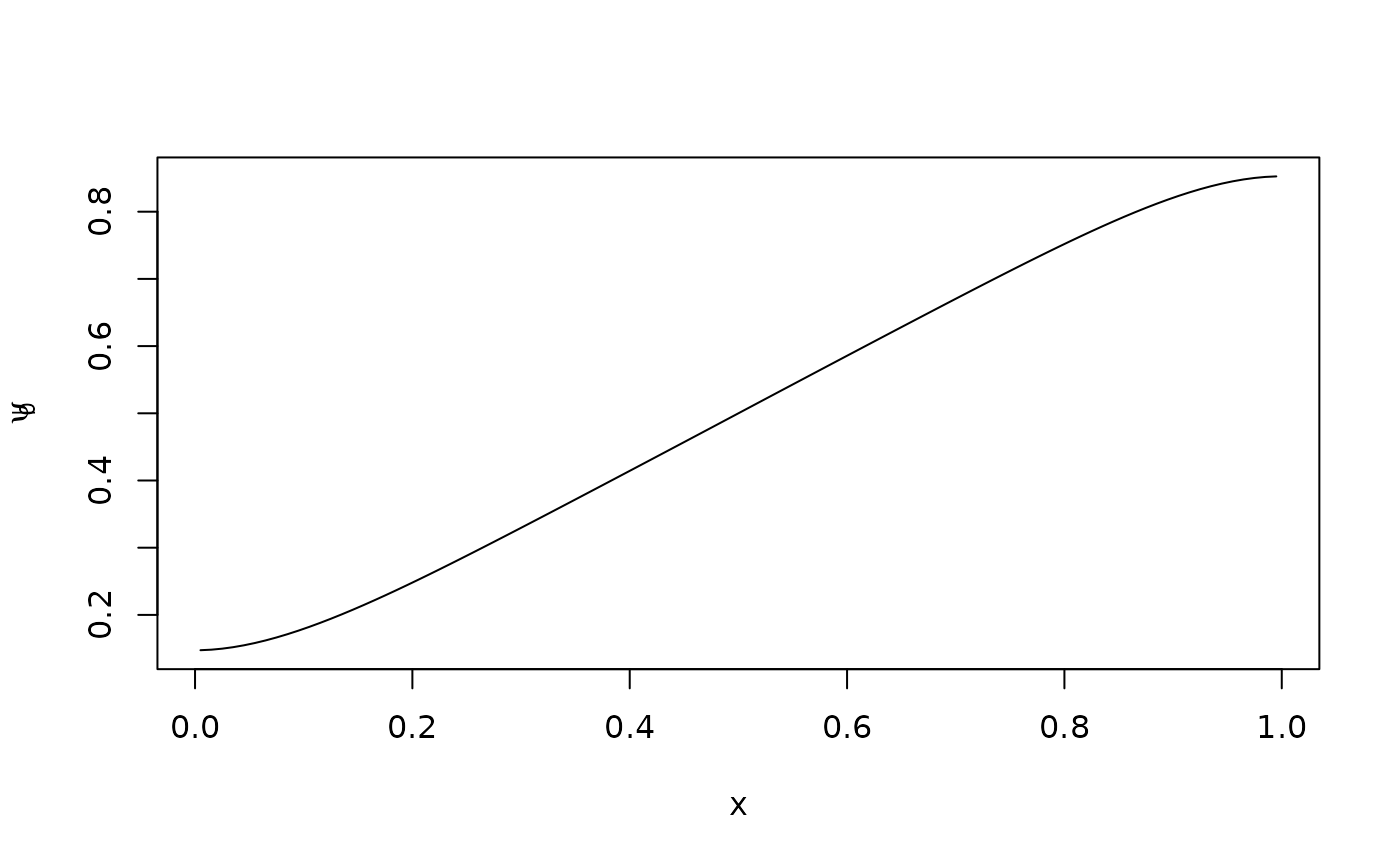

The backward equation

The backward Kolmogorov equation in advection-diffusion form is and when we discretize this, it yields the same generator as the forward equation, but now we view the matrix as an operator on column vectors. For example, we can find the expected value of , as a function of the initial condition :

psit <- as.numeric(xc)

psi0 <- expm(G*t) %*% psit

plot(xc,psi0,type="l",xlab="x",ylab=expression(psi[0]))

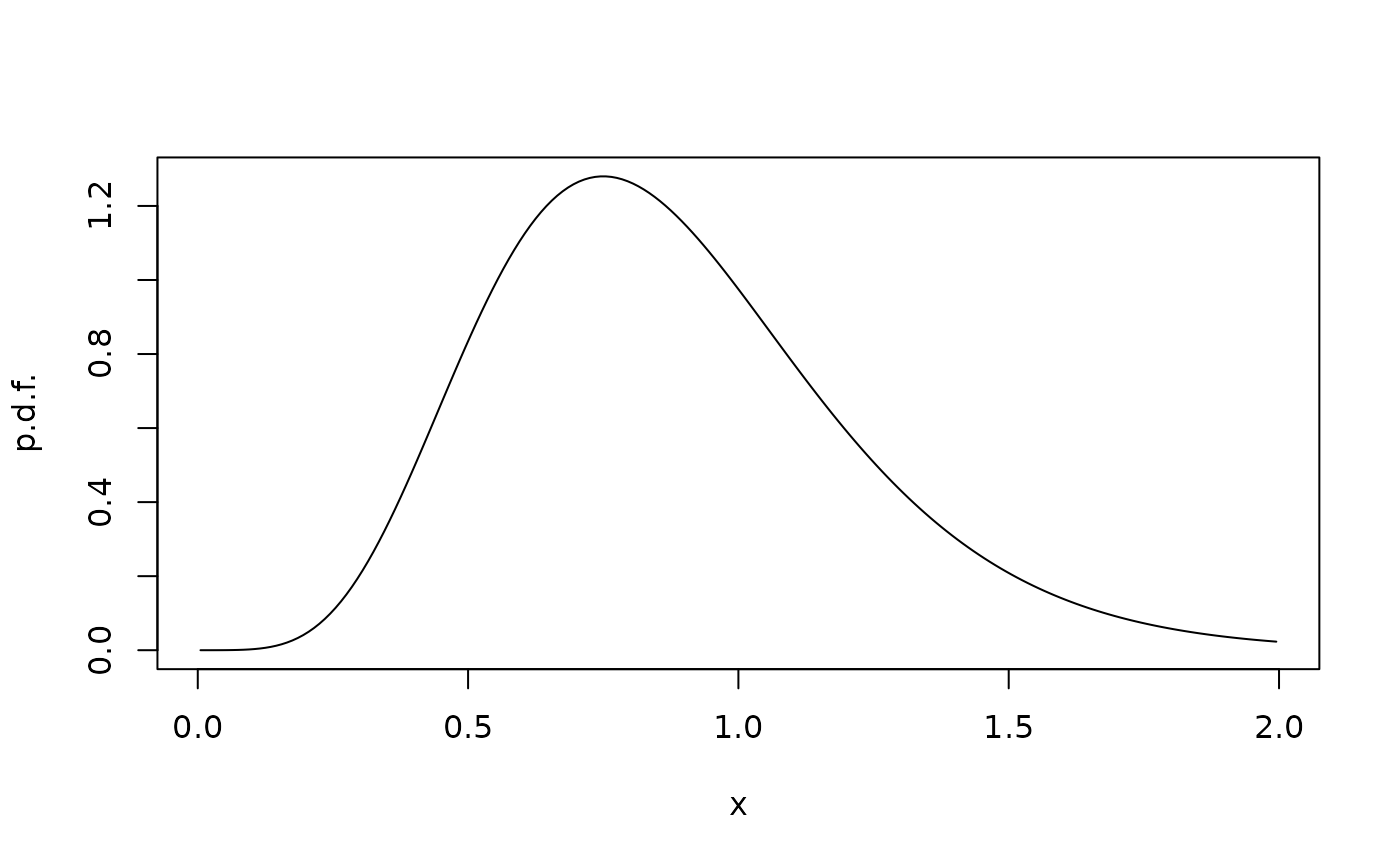

Varying diffusivity

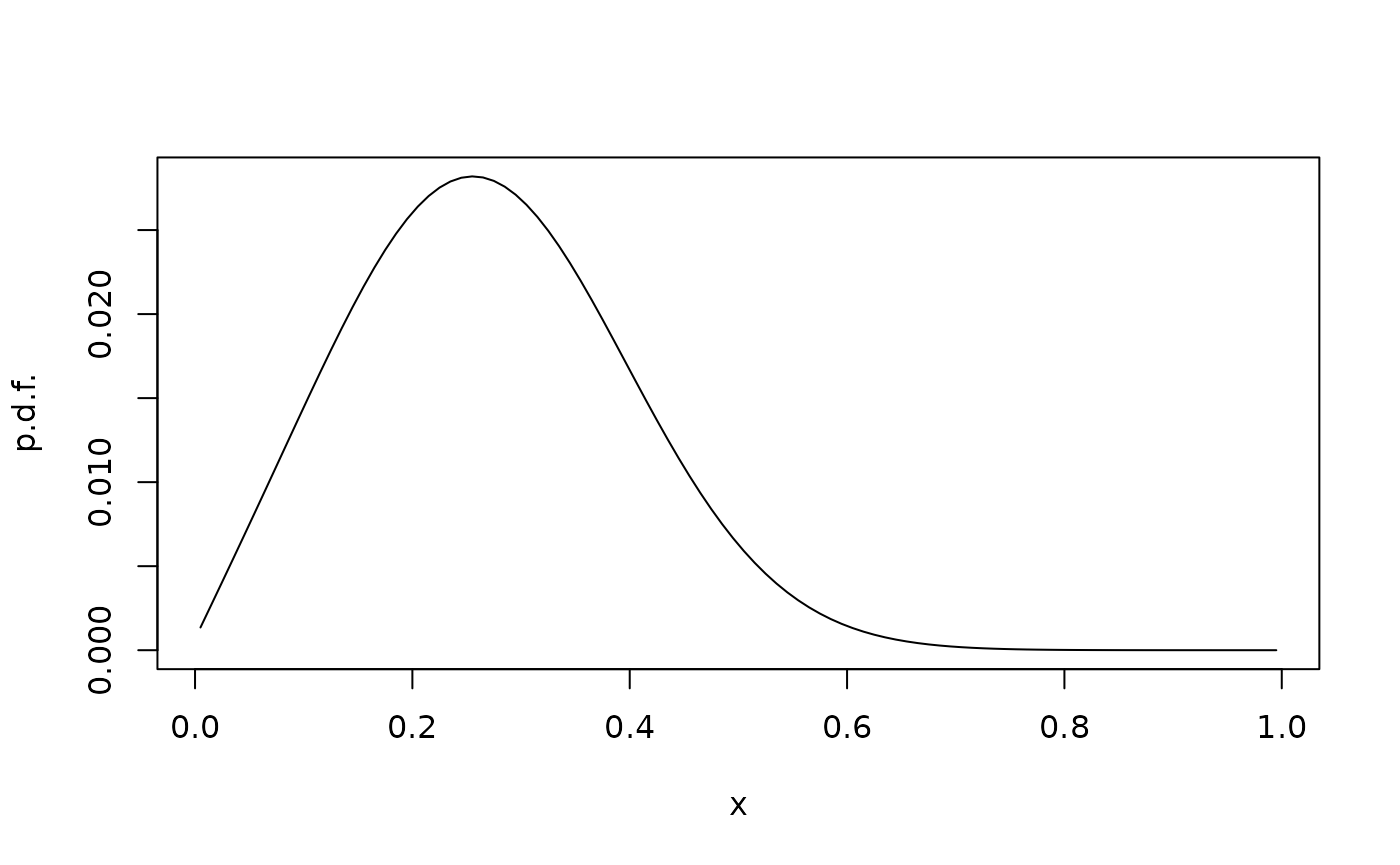

Keep in mind that when the diffusivity varies in space, the drift field in the stochastic differential equation does not equal the advective field . Rather, with the SDE we have the forward equation where advection and diffusion can be found from drift and noise intensity as The code fvade uses the advection-diffusion formalism. For example, for stochastic logistic growth where and :

sigma <- 0.5

f <- function(x) x*(1-x)

g <- function(x) sigma * x

gp <- function(x) sigma ## Implements the derivative g'(x)

D <- function(x) 0.5 * g(x)^2

Dp <- function(x) g(x)*gp(x) ## Implements D'(x)

u <- function(x) f(x) - Dp(x)

xi <- seq(0,2,0.01)

xc <- cell.centers(xi)

G <- fvade(u,D,xi,'r')

rho <- StationaryDistribution(G)

plot(xc,rho/diff(xi),type="l",xlab="x",ylab="p.d.f.")

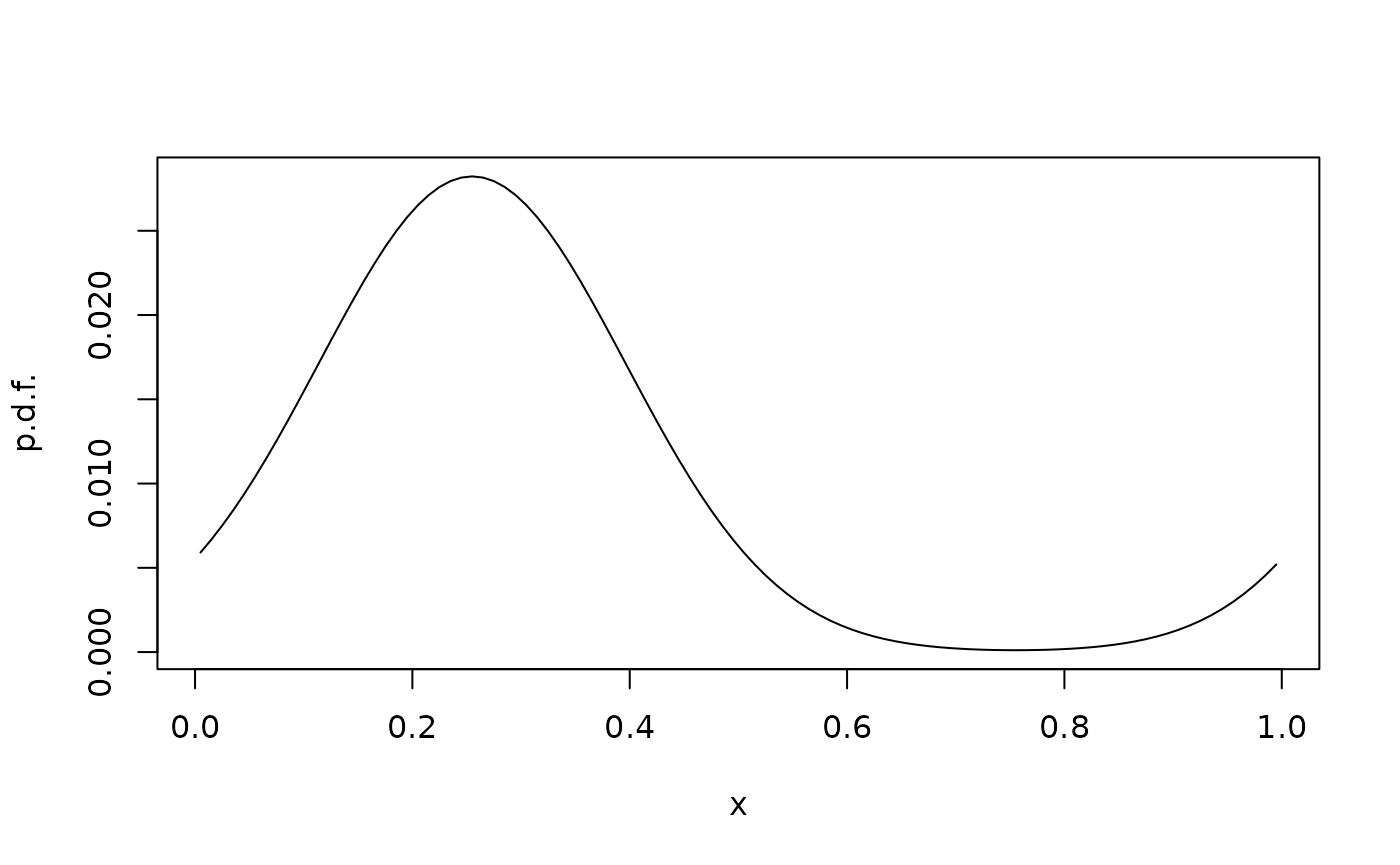

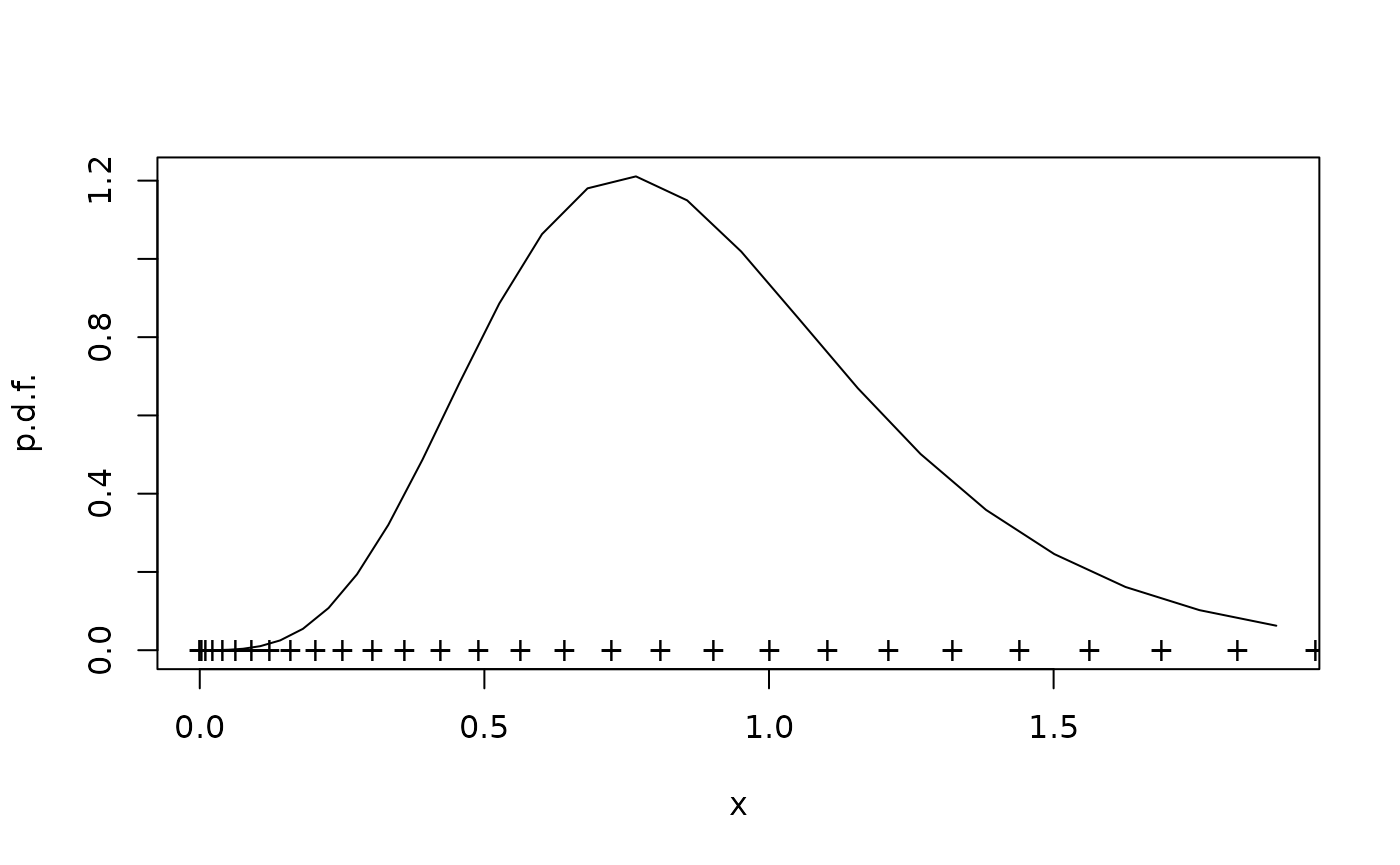

Non-equidistant grids

Sometimes it is an advantage to use higher spatial resolution in some regions of state space. In this case it is extra important to keep in mind that fvade works on probabilities of each grid cell, not densities:

xi <- seq(0,sqrt(2),0.05)^2

xc <- cell.centers(xi)

G <- fvade(u,D,xi,'r')

rho <- StationaryDistribution(G)

plot(xc,rho/diff(xi),type="l",xlab="x",ylab="p.d.f.")

points(xi,0*xi,pch="+")

This grid is a bit coarse, so the spatial discretization error is there, but demonstrates the principle.